The Case of Najma Saʿīd Ismāʿīl: A ‘Proof of Ownership’ Document Issued by the Islamic State (2016)

Laura Emunds is a PhD candidate at the University of Bern, where she conducts her research in the TraSIS team.

We recommend that readers explore our other blog contributions which are linked here.

Content note: the source discussed in this month’s blogpost originates from the context of the most recent genocide of the Yezidi people and speaks about the sale of a woman enslaved by the so-called Islamic State. This post therefore contains material of a sensitive nature, and reader discretion is advised.

Introduction

Among scholars working in the field of Slavery Studies and related areas, one of the most pressing questions in recent years concerns the difficulty of labelling the diverse phenomena we see: when is it appropriate to speak of slavery? When do we refer to bondage? What role does labour coercion play? To mention only two important approaches discussed in the last couple of years: is it more useful to focus in our analyses on social relations shaped by ‘strong asymmetrical dependencies’, as has been suggested by a number of scholars working at the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies (BCDSS)?[1] Or do we identify slavery as ‘a very old snake’ that shed its skin countless times, as Michael Zeuske (also a member of the BCDSS) has put it?[2] Whatever decision we as individual scholars take in this regard, and this is certainly always highly dependent on our particular questions and contexts, the importance of the question of legal ownership of the bodies of unfree human beings throughout history can hardly be denied. The most recent despicable example of this importance is the abduction and enslavement of more than 6,000 Yezidis, men, women, and children of all ages, inseparably linked to the genocide of their people that began after the fall of Mosul to the fighters of the self-proclaimed caliphate of the Islamic State in summer 2014.[3]

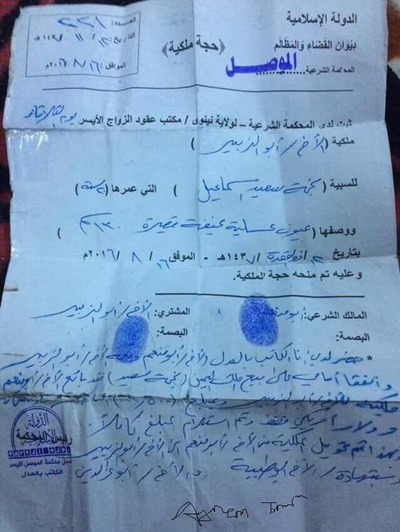

The source I explore in this blogpost is a legal document issued by the authorities of the Islamic State in Mosul, Iraq, in August 2016. More precisely, it is a ḥujjat milkiyya, a ‘proof of ownership’, that serves the purpose of establishing legal possession of an enslaved woman named Najma Saʿīd Ismāʿīl by a man referred to as ‘the brother Abū l-Zubayr’.[4]

Elsewhere, TraSIS team member Omar Anchassi has written about the introduction of slave concubinage by the self-proclaimed caliphate and has examined the connection of this phenomenon to the corpus of premodern jurisprudential literature, and to the group’s eschatological frame of reference.[5] Here, however, I would like to draw the reader’s attention to the following questions: firstly, what kind of information does this ‘proof of ownership’ document contain? What structure does it follow? And secondly, what insights can we gain into the enslavement practices carried out by the Islamic State through analysing it?

Structure and Content

The document consists of three vertically arranged sections which are separated from each other by two printed lines: one completely solid line between the first and the second section, and another line that separates the second and the third part stretching from the right side until a little beyond the middle of the paper.

The first part of the document covers around one-fifth of the total area and is very formalistic: it states the document type, the authority by which it has been issued as well as the place and hijrī and Gregorian dates on which this took place. Additionally, we find a consecutive number. Building on this information, we know that this document is a ḥujjat milkiyya, a ‘proof of ownership’, that has been assigned the consecutive number 221 and was issued on the 12th of Dhū l-Qaʿda 1437h, corresponding to 16th August 2016. The issuing authority is the Islamic State (Ar. al-dawla al-islāmiyya), specifically its ‘dīwān al-qaḍāʾ wa-l-maẓālim’, which can be translated as the ‘Bureau for the Judiciary and Grievances’. While the term qaḍāʾ suggests regular Sharia courts presided over by qāḍīs, the term maẓālim signifies ‘the structure through which the temporal authorities took direct responsibility for dispensing justice.’[6] It often involved the executive power acting In consultation with religious elites, and the venue for dispensing this form of justice could be a ruler’s palace or some separate building erected specifically for this purpose.[7] It is unclear how the qaḍāʾ–maẓālim distinction functioned in the context of the Islamic State.

The middle part of the document covers the following two-fifths and contains the actual ‘proof of ownership’, establishing the legal owner of the enslaved women in question. The enslaved woman is identified by her name, physicalappearance, and age. This part of the document repeats the date on which it was issued. What we read here is: ‘[The following] has been established before the Sharia court of Nineveh Province at the office for marriage contracts (on Tuesday): the ownership of brother Abū l-Zubayr of the female captive (Ar. sabiyya) Najma Saʿīd Ismāʿīl, aged 20 years. Her description: honey-coloured eyes, thin, short, 130cm. On the date: 12th of Dhū l-Qaʿda 1437 hijrī, corresponding to 16/8/2016 mīlādī. He has been issued this proof of ownership.’

The lower two-fifths of the document can be further sub-divided into two: firstly, in the part that follows directly after the second line mentioned above, we find the opportunity to name the former owner of the enslaved person, who is denoted here as ‘al-mālik al-sharʿī’, the rightful owner, and the purchaser, ‘al-mushtarī’. Both sign the document in this section with their fingerprints, as required by the form. Here, we learn that the former owner was a certain Abū Munʿim and that Abū l-Zubayr, for whom the proof of ownership is issued, is the one who purchased Najma Saʿīd Ismāʿīl from him. Below this last formulaic part, we find a blank section preceded by an asterisk. This space has been used for an additional comment, written by a certain ‘al-kātib bi-l-ʿadl’, the person responsible for scribing the document (the phrase refers to Qurʾān 2:282). He states that the two men, Abū Munʿim and Abū l-Zubayr, contracted the sale of Najma Saʿīd Ismāʿīl in front of him. Najma is classified here as ‘milk al-yamīn’, meaning ‘property of the right hand’, a Qurʾānic expression referring to slave concubines. He also mentions the price of $1,500 USD, which had already been paid in its entirety when the document was issued. Because of this, the scribe states that the transfer of ownership to Abū l-Zubayr has been completed. Finally, it is noted that this has been witnessed by a certain Abū Ṭayyiba and another man called Abū ʿIzz al-Dīn.

In the lower lefthand side, the document includes a stamp that identifies it as being issued by the Islamic State and as part of the court records of Mosul. The stamp also includes ‘al-kātib bi-l-ʿadl’.

Analysis

It is very important to consider documentary and archival evidence in the study of legal phenomena in order to bridge the oft-criticised gap between juristic theory and practice. It is difficult, however, to draw compelling conclusions from a single document. Nevertheless, I would like to take the opportunity to point to some aspects of the attitude of IS personnel toward persons abducted and enslaved by them, based on this document.

The overall impression given by the document is that slavery in the Islamic State was a highly regulated and well-administered field. What we are dealing with in this case is a form printed to facilitate the Islamic State’s issuing such ‘proofs of ownership’, standardising the procedures of their courts. This is indicated by the document’s design: the first and second part in particular can be filled in very quickly, with the decade pre-printed so that only the correct year need be indicated by hand, in addition to the day and month. The name of the court is also stamped on the document, as well as the consecutive number (221), indicating not only the demand for such ‘proofs’, but perhaps also something, admittedly vague, about the court’s caseload, and perhaps even the size of the enslaved population in the province.

Further noteworthy observations can be made when we focus on the second part of the document. Here, we learn that the office responsible for issuing the document within the structures of the court in Mosul was the one for matters of marriage.[8] This part of the document also sheds light on the identity of the man for whom this ‘proof’ was issued, as well as that of the enslaved woman (and the commodification of her body). The man is only identified as a certain ‘brother Abū l-Zubayr’, which is rather vague. The enslaved woman, on the other hand, is characterised by the form as a sabiyya, a female abducted in warfare. This term is frequently encountered in other publications of the Islamic State.[9]We also learn her name, Najma Saʿīd Ismāʿīl. The document adds that she was 20 years old when the document was issued in August 2016. The form requires a further description of her: in this respect, the document accords well with premodern purchase deeds I have analysed elsewhere,[10] in that only Najma’s physical appearance is described, rather briefly. Character traits and behaviour do not figure at all. This emphasises the commodification of her body through enslavement and the related legal procedures, such as her being the object of a commercial transaction.

In the document’s final part, the form details the former ‘rightful’ owner and the purchaser. This offers us some context for the preceding section: it becomes clear that the ‘proof of ownership’ was issued because a transaction took place in which Najma was sold by a certain Abū Munʿim to her new owner, Abū l-Zubayr. In the following handwritten statement, the document’s scribe confirms this, including a mention of the price that had been paid, $1,500 USD. Due to the reportedly large price differences for enslaved Yezidis, ranging from less than $20 USD to more than $12,000 USD, it is not possible to interpret the significance of this figure without further context.[11] Finally, the transaction is attested by two witnesses, though they have not signed the document themselves. This distinguishes them from the seller and buyer, who have signed with their fingerprints, as per the requirements of the form.

Conclusion

While analysing a single document might be unsatisfactory when it comes to drawing larger conclusions, the ‘proof of ownership’ explored here bears witness to the fact that still, even in the 21st century, people can suffer from abduction and enslavement. This genocide of the Yezidi people has shown that the dehumanisation of fellow human beings, thecommodification of their bodies and the neglect of their personhood is by no means over. The phenomena we study are not confined to some distant past, but manifest themselves in a variety of ways as part of our present.

Bibliography

Ali, Kecia. 2010. Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Anchassi, Omar. 2020. “The Logic of the Conquest Society: ISIS, Apocalyptic Violence and the ‘Reinstatement’ of Slave Concubinage,” in Violence in Islamic Thought From European Imperialism to the Post-Colonial Era, ed. By Mustafa Baig and Robert Gleave, 225–248. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Emunds, Laura. 2022. “Framing the ‘Human Commodity’: Descriptions of Enslaved Bodies in Purchase Deeds from the 3rd/9th to the Early 10th/Late 15th Century.” Studi Maġrebini 20, 2: 166–186.

Nicolaus, Peter and Serkan Yuce. 2017. “Sex-Slavery: One Aspect of the Yezidi Genocide.” Iran & The Caucasus 21, 2: 196–229.

Nielsen, Jørgen S. “Maẓālim.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0721 (accessed 10 March 2023).

Rapoport, Yossef. 2012. “Royal Justice and Religious Law: Siyāsah and Shariʿah under the Mamluks.” Mamlūk Studies Review 16: 71–102.

Umm Sumayyah al-Muhājira. 1436 [2015]. “Slave-Girls or Prostitutes?” Dabiq 9: 44–49.

Winnebeck, Julia et al. 2023. “The Analytical Concept of Asymmetrical Dependency.” Journal of Global Slavery 8: 1–59.

—. 2021. On Asymmetrical Dependency, Concept Paper 1. Bonn, Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies. Available at: https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/images/pdf-files/bcdss_cp_1-_on-asymmetrical-dependency.pdf (accessed 10 March 2022).

Zeuske, Michael. 2021. Sklaverei. Eine Menschheitsgeschichte von der Steinzeit bis heute. Ditzingen: Reclam.

I would like to thank Serena Tolino for her feedback concerning the sensitivity of the discussed source and Omar Anchassi for not only sharing his expertise with me, but also for his careful language editing.

[1] Initially suggested in Julia Winnebeck, J. et al. 2021. On Asymmetrical Dependency, Concept Paper 1. Bonn, Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies. Available at: https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/images/pdf-files/bcdss_cp_1-_on-asymmetrical-dependency.pdf (accessed 10 March 2022). See also the following article which builds on this first publication: Julia Winnebeck et al. 2023. “The Analytical Concept of Asymmetrical Dependency.” Journal of Global Slavery 8: 1–59.

[2] Michael Zeuske. 2021. Sklaverei. Eine Menschheitsgeschichte von der Steinzeit bis heute. Ditzingen: Reclam, 17.

[3] Peter Nicolaus and Serkan Yuce state that the total number of abducted Yezidis was 6,396. In October 2016, two years after the fall of Mosul, 3,799 of them were still hold in captivity and enslavement according to their data. See: Peter Nicolaus and Serkan Yuce. 2017. “Sex-Slavery: One Aspect of the Yezidi Genocide.” Iran & The Caucasus 21, 2: 200.

[4] The document has been published as specimen 36L by Aymenn Jawad al-Tamini on his blog, see https://www.aymennjawad.org/2016/09/archive-of-islamic-state-administrative-documents-2 (accessed 31 March 2023). I thank Aymenn for giving me the permission to use this document.

[5] Omar Anchassi. 2020. “The Logic of the Conquest Society: ISIS, Apocalyptic Violence and the ‘Reinstatement’ of Slave Concubinage,” in Violence in Islamic Thought From European Imperialism to the Post-Colonial Era, ed. By Mustafa Baig and Robert Gleave, 225–248. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

[6] Jørgen S. Nielsen, “Maẓālim.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0721(accessed 10 March 2023).

[7] Yossef Rapoport. 2012. “Royal Justice and Religious Law: Siyāsah and Shariʿah under the Mamluks.” Mamlūk Studies Review 16: 81.

[8] This institutional structure might hint at the conceptual similarities of marriage and slave concubinage rooted in the Islamic legal tradition, a topic that has been discussed in great depth by Kecia Ali. See: Kecia Ali. 2010. Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

[9] Umm Sumayyah al-Muhājira. 1436 [2015]. “Slave-Girls or Prostitutes?” Dabiq 9: 44–49.

[10] Laura Emunds. 2022. “Framing the ‘Human Commodity’: Descriptions of Enslaved Bodies in Purchase Deeds from the 3rd/9th to the Early 10th/Late 15th Century.” Studi Maġrebini 20, 2: 166–186.

[11] Nicolaus and Yuce, “Sex-Slavery,” 199.